Below is a list of some research papers written about Queen’s Market (Source of list: Markets 4 People/ University of Leeds report 2021):

• NEF (2006) The World On A Plate –The economic and social value of London’s most ethnically

diverse street market: https://neweconomics.org/2006/05/the-world-on-a-plate

• González, Sara (2017) Contested Markets, Contested Cities – Gentrification and Urban Justice in Retail Spaces: https://www.perlego.com/book/1499591/contested-markets-contested-cities-gentrification-and-urban-justice-in-retail-spaces-pdf

• Dines, Nick. 2007. The Experience of Diversity in an Era of Urban Regeneration: The Case of

Queens Market, East London. EURODIV Working Paper 48. Milan: Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei

(FEEM).

• Bartholomew, M. (2018). Revisiting ‘Rubbing Along’: Contact, Cohesion and Public Space – A Case

Study of Queen’s Market, Newham. Dissertation submitted for the MSc City Design and Social

Science, London School of Economics and Political Science.

• Regenerating London: Governance, sustainability and community in a global city (Routledge 2009). Edited by Rob Imrie, Loretta Lees and Mike Raco. Link: https://www.academia.edu/9454478/The_disputed_place_of_ethnic_diversity_An_ethnography_of_the_redevelopment_of_a_street_market_in_East_London

• Jatoonah, J. (2018) Shopping, place, identity: Investigating spaces of consumption and

gentrification in Newham (undergraduate dissertation, King’s College London)

• Fulford, W. 2005. A Study of Urbanity and Markets. Dissertation submitted for the MA in Urban

Regeneration at Westminster University.

• Queen’s Market: an exploration of neighbourhood and locality. Undergraduate dissertation,

Heritage Globalisation and Development.

• Queen’s Market also features as a case study in numerous reports (eg Bua, Taylor and Gonzalez

(2018) Measuring the value of traditional retail markets: towards a holistic approach; Community

Links (2015) Incidental connections: an analysis of platforms for community building; Demos

(2007) Equally Spaced? Public space and interaction between diverse communities.

Queen’s Market: a successful and specialised market serving diverse communities in Newham and beyond (2021)

Watson S, González S, Newing A, Buckner L and Wilkinson R. 2021.

The disputed place of ethnic diversity: an ethnography of the redevelopment of a street market in East London (2009)

Section written by Nick Dines

Introduction

Considerations on the position of markets in contemporary London

It is a blustery but sunny Saturday afternoon in early December. Queens Market is packed with people going about their weekend shopping trips. The smells of fish, meat and coriander waft through the air as the solitary cries of traders are drowned out by the multilingual chatter. Four Black Caribbean men in their sixties hanging outside a kiosk taunt a fruit and veg trader about West Ham United’s latest plight in the Championship. Groups of Asian and African women chat as they rummage through rolls of material on a stall tended by two young white men. In front of the canopy a few people are collecting signatures to “save Queens Market”. One of them, a middle-aged Asian man, is relaying information in Hindi through a megaphone. Discarded empty boxes are littered around stalls and a number of plastic bags eddy in the aisles. In a quiet square adjoining the market, a few people are milling around a caravan belonging to a property development company. An exhibit has been erected displaying designs for a new complex featuring a superstore, a new market, shops and apartments. Leaflets are being handed out to the few passers-by, asking for their thoughts on the plans. Printed on the front of them are the words: “The New Queens Market. Towards a Safe, Clean, Vibrant and Lively Shopping and Living Environment”. [Field notes, December 2004] Queens Market has operated next to Upton Park tube station in Newham, East London for just over a century (see figure x.1). Since 1968 the market has been located underneath a purpose-built, open-ended steel and concrete structure which currently houses eighty stalls trading four days a week as well as a series of independently run shops and kiosks (see figure x.2). Besides providing residents with cheap food and household goods, Queens Market has long been a focal point for minority groups, from East European Jews and Germans at the beginning of the twentieth century to the Caribbean and South Asian groups who started to arrive after the Second World War to more recent migrants such as West Africans and East Europeans.

The London Borough of Newham (LBN) has the highest non-white population of any local authority area in the United Kingdom. According to the 2001 census, 60.6% of its 237,900 residents were from Black and Minority Ethnic groups, compared to 7.9% nationally and 28.8% in London. In contrast to the neighbouring borough of Tower Hamlets with its large Bangladeshi population, the ethnic minority composition is extremely diverse. The principal ethnic groups are: Black African (13.1%); Indian (12.1%); Bangladeshi (8.8%); Pakistani (8.4%) and Black Caribbean (7.3%). The borough’s dense web of social networks and relatively cheap housing has meant that it remains a first point of arrival for refugees and migrants. Newham’s “super-diversity” (Vertovec 2006) is most vividly captured in Queens Market. Indeed, the market is often locally considered to be the “multicultural” hub of Newham on account of its particular history, the variety of ethnic products on sale, the mix of people who trade and shop there, and the fact that it lies at the geographical centre of the borough. In September 2004 the Labour-run local authority announced plans to demolish Queens Market and rearrange it within a new shopping precinct. Promoters of the scheme argue that the current market is unsafe and dirty as well as a drain on the council’s limited resources. Redevelopment of the site, to be financed and carried out by a private developer, would instead provide Newham residents with improved housing and retail facilities and at the same time attract new people and businesses to the borough. During the same period, an umbrella group called ‘Friends of Queens Market’ (FoQM), consisting of shoppers, traders, community organisations, opposition councillors and local political parties, has coordinated opposition to the scheme and has instead called for refurbishment to the existing structure. As well as emphasising its continuing popularity, campaigners have made a point of celebrating the particular cultural diversity of the current market. This, they feel, would be irrevocably lost in the event of redevelopment. The market offers a particular lens through which to explore struggles over the meaning and shape of public space in contemporary London. Until recently, scarce attention has been paid to street markets in the literature on regeneration in the UK. Yet markets have historically played a key role in British urban life as sites of commerce, consumption and social interaction (Watson and Studdert 2006). As distinct public spaces and crucial nodes in people’s social and economic networks, they have also been closely bound up with notions of place identity, particularly so in London (Sinclair 2006). However, as Stallybrass and White (1986) remind us, the market has held a somewhat equivocal position in the modern city: “A marketplace is the epitome of local identity (often indeed it is what defined a place as more significant than surrounding communities) and the unsettling of that identity by the trade and traffic of goods from elsewhere. At the market centre of the polis we discover a commingling of categories usually kept separate and opposed: centre and periphery, inside and outside, stranger and local, commerce and festivity, high and low” (Stallybrass and White 1986, p.27). This inherent promiscuity of the market can create feelings of anxiety by disturbing a sense of order (Sibley 1995), but may also be a source of attraction by providing a less regulated social realm than other spaces of the city. In addition, the market has traditionally been a politically ambivalent space; on the one hand functioning as an inclusive everyday public sphere, while on the other representing a place of petty bourgeois reaction and nostalgia (Watson and Wells 2005). The key question that needs to be asked is, if the market has constituted a particular experience at the city’s core, one that is both mundane and exceptional, what might its ‘regeneration’ entail? During the last two decades there has been a narrative about the decline of markets. Traditional markets have found themselves closed down, under threat or relocated outside urban centres, largely as a result of growing competition from superstores and out-of-town shopping malls and a lack of investment from local authorities which have redirected finances towards higher priorities such as housing and education (Watson and Studdert 2006). However, the idea of ‘decline’ is at the same time problematic. Conceived simply as a drop in customer footfall, it overlooks the ongoing, less tangible social role of markets. The term can also be used to simply express a negative evaluation which positions a market in relation to transformations that have occurred in a surrounding area. For example, Jane Jacobs discusses how the allure of the fruit and vegetable market in Spitalfields, East London swiftly diminished for new middle-class residents as its noise and clutter began to disturb their gentrified vision of turning the district into “a restored monument to early Georgian London” (Jacobs 1996, p.85). As such, the notion of ‘decline’ is employed to legitimate that other powerful metaphor, ‘regeneration’ (Furbey 1999). More recently there has been an equally insistent narrative of ‘revival’. The demise of street markets has been checked in the last decade by a growth in popularity of specialist and farmers’ markets, although these have tended to attract a more affluent public and have been unsuccessful in ethnically diverse parts of London (Watson and Studdert 2006)[1]. In order to revitalise trade, existing markets, such as Queens Crescent market in Gospel Oak and Broadway Market in Hackney, have begun introducing new stalls selling international gourmet foods and handicrafts in order to attract higher-income residents who have moved into the local area. This has sometimes given rise to tensions between ‘indigenous’ market users and newcomers around questions of cost and taste and, where increased popularity has attracted major property investors, has led to outright conflict,as in the case of the protracted ‘Battle of Broadway Market’ between 2005 and 2006 when residents and activists physically resisted the eviction of a local café owner (Kunzru 2005; Iles and Seymour 2006). During this period of ‘decline’ and ‘revival’, urban policy has paid scant attention to street markets. Despite growing cross-departmental interest in the public realm under the Labour Government and the inclusion of markets in its planning agenda for town centres (ODPM 2005), there has been little emphasis on understanding how markets function as social spaces. In response to this policy gap, a number of recent studies have sought to highlight the benefits of markets; underlining, for instance, the opportunities they offer for social interaction and inclusion (Taylor et al. 2005; Dines et al. 2006; Watson and Studdert 2006). In a global metropolis like London, markets are seen to serve a diverse public and to act as entry points for new arrivals. As the authors of a report produced for the London Development Authority remarked, “markets create a sense of neighbourhood and social capital that can be difficult to find in London” (Taylor et al 2005, p.44). The reports have all called on local authorities to strengthen their support for markets by incorporating them within sustainable community, social inclusion and

[1] First established in 1997, by definition a farmers market in London is where producers from within 100 miles of the M25 motorway sell their produce direct to the public. Watson and Studdert note that part of the reason why attempts to introduce a farmer’s market in Tower Hamlets were unsuccessful was because the local Bengali population wanted to buy products from Bangladesh. (2006, p.32).

‘Regenerating London’ is available to buy from:

http://books.google.it/books?id=P3LJvdkJbC8C&dq=Regenerating+London+%2B+Imrie&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=Y91YNKV_HH&sig=XRfc_dIUDBNMlZ3obxxrq-QO5k0&hl=it&ei=XhKlScOyIcOg_gaHv-2XBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result

[**to be published in R. Imrie, L. Lees & M. Raco, eds, Regenerating London. Governance, Sustainability and Community in a Global City. London, Routledge, 2008.]

Examples of books and reports that write about the value of Queen’s Market:

“The crowds were thickest outside Queen’s Market, a cacophony of stalls close to the station.

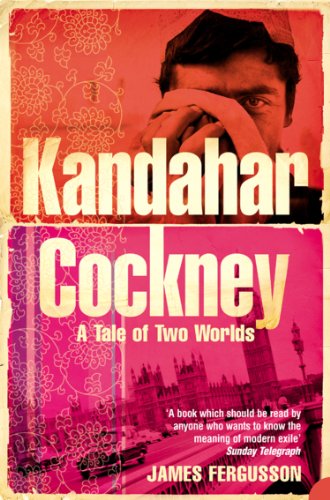

……Mir was waiting, but a closer look at this market was irresistible. I strolled with my helmet through the stalls, inhaling Central Asia again, feeling like an alien in the city of my birth. Women in saris swarmed around the vegetable stands, bargaining with the stall-holders, sifting through the foodstuffs with practised brown fingers. Among the recognisable goods were species of vegetation that were new to me – mooli and tindora, papadi and cho-cho, patra and parval, long dhudi, posso, china karella. There were over a dozen types of flour with names like dhokra and dhosa mix, mathia and oudhwa, mogo, rajagro, singoda. There were packets of moth beans and gunga peas, sliced betelnut and sago seeds. There was a mouth freshener called mukhwas manpasand, and something called red chowrie, that was not to be confused with brown chorie, which according to the label was also known as pink cow peas.”

Quoted from Kandahar Cockney by James Fergusson

(Harper Collins, 2004)